Let’s say that you’re shopping around for a new big screen TV, because football season has kicked off and they’re already hitting the ice with the NHL pre-season. You come across an advertisement for one of your local electronics stores, saying that they have one of the best models on sale this weekend, but they have a limit of just five units per location. You really want that TV, so you get to the store bright and early on Saturday morning.

But what if that “sale price” is just a ruse and the TV really isn’t all that much cheaper than it is regularly at that store? What if you can actually get a better TV for less money from a competitor, but the other store failed to advertise this fact? This is the critical difference between the actual reality of the situation and your perceived reality based on the facts that you have (and have not) collected.

It’s called scarcity. The rarer or seemingly more difficult it is to obtain something, the more that people will desire that something. Diamonds are so expensive, because they are perceived to be rare by the general public. This, along with your big screen TV, almost makes sense, because they are both physical items and they could really run out of them. Making something appear scarce or rare can make them more desirable than something that appears to be plentiful and easily acquired.

However, it doesn’t always work that way.

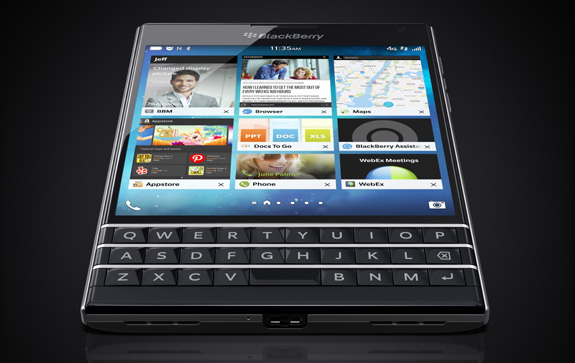

You may have heard that pre-orders for the BlackBerry Passport smartphone sold out in the first day. Or maybe you didn’t hear about that, because far fewer people are interested in the new BlackBerry than they may be interested in a new Nexus or a new iPhone. Just because the Passport is seemingly playing hard to get doesn’t mean that more people will actually want it. And let’s not forget that BlackBerry didn’t even say how many of these phones they had available in the first place; it could have been a very small batch. By contrast, the scarcity dynamic seems to have worked with the invite-only OnePlus One. They drummed up a lot of interest by making the phone more difficult to get.

So, how does this apply to the world of Internet marketing and digital products? If you are selling an e-book, you theoretically can never run out of stock. It doesn’t matter how many people buy your book on Kindle, Amazon can continue to sell more and more. That may sound great, but it could also have a reverse effect: things that are easy to acquire may not ever get acquired in the first place.

If a customer knows that a product (or service) will always be there and will always be available for purchase, he or she could run into the mentality of “I’ll get it tomorrow” or “I’ll get it some day.” And then, he or she will forget about it and you’ll lose out on the sale. By saying that the product is only available for the next 24 hours (the Woot model) or only to the next X number of buyers (the Groupon model), you could generate far more interest.

And since you are no longer going for sheer quantity anymore, it becomes even more important that you sell those customers on your big ticket offer to maximize your profit. Your product is perceived to be scarce and, given the right circumstances, it can then be perceived to be remarkably valuable. Of course, people have to be at least interested in what you have to offer in the first place.

Get John Chow’s eBook and Learn How To Make Over $100,000 a Month